How did the idea of writing this book come to you? What made you decide to write this?

It’s a book about my father. He died unexpectedly in 2008. He was on a train on his way to Bombay (Mumbai) to participate in a play that he had a starring role in. He died on the train at 4 am in the middle of the country, at eighty-seven years old. Luckily, I was in India at that time, but it was still a big event to get his body back.

The fallout from his death was that a lot of things had to be done to look after his affairs and over the years to look after his archive, which was extensive. He, of course, did not organize anything, so I started to do it slowly over the years. Three years ago, one summer, I went to India to dedicate myself to the task of simply organizing his archive. Luckily, I found a Ph.D. student from Michigan who was interested in architecture and wanted to join me. There was also a recent graduate from RISD who showed up in Chandigarh, my hometown in India. He didn’t know what to do, so I said “I got something for you to do”. And there was a former student from here, the University of Washington, who did her MS in History and Theory with me and worked on my father’s work. She was in India and offered to help. The three of them and I camped out in the archives, literally amongst the things, and dedicated ourselves to organizing these papers. It turned out there were over 1,000 architectural drawings, about 200 paintings, 600 art drawings, archival photographs, all kinds of things. I even found a regional, local museum drawing in his papers. It’s just an incredible treasure trove. (This archive has now been acquired by the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal.

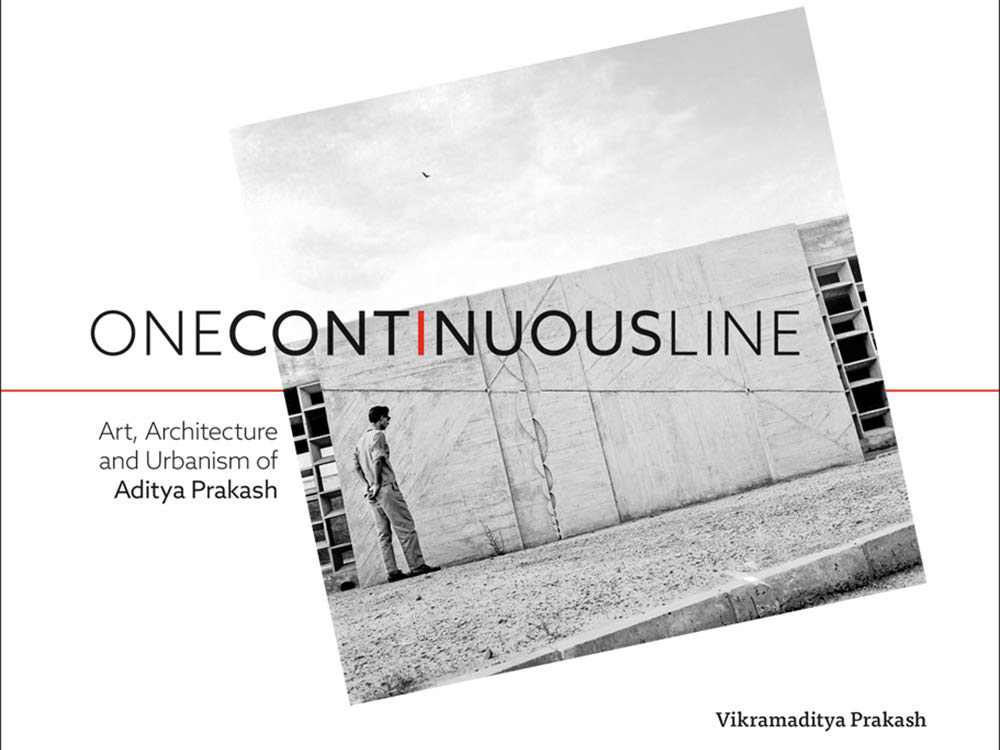

In doing that I decided to make a selection out of these archives and see if we can have them published. I started to write an Introduction to this publication, initially thinking it would be a short text of around 5,000 to 10,000 words. Bipin Shah of Mapin Publishing came to Chandigarh while we were camped out there among the archives and he said “you’ve got to do this book and you’ve got to do it properly, you can’t just do a little pamphlet.” Next thing I knew it was 50,000 to 60,000 words and it had become a full-fledged book.

I went back to the US and circulated the text that I had, amongst friends and colleagues. I was really worried that since he’s my father, this would appear to be a vanity piece, which I hate. They gave me good, critical feedback and said that overall it felt like a history of his life. One piece of feedback I received was that I needed to write a critique of his work, so I developed the last chapter into a long critique. Basically, that’s how the book came about.

When you see the book, you will see it’s beautifully designed — it’s just a gorgeously laid out book, an amazing production job. Mapin hired a designer from New Delhi, India. When he took on the job he said,” I know you” and I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “I went to the University of Washington.” It turned out that he was majoring in computer science and as part of his distribution requirements took one of my courses. One day he was hiking and had a near-death experience that forced him to re-evaluate his life. He said, “what am I doing with this computer science stuff? I just want to be a designer.” That’s how he went on to become a graphic designer instead. Ishan Khosla is his name.

Once he took on the book, Ishan came lived in the house with me and all my father’s archives. Surrounded himself by it. He poured his heart and soul into the design of the book.

It's just something I started to write and next thing I knew it had become this big thing.

Do you know of any other books where a child is critiquing their parents’ work?

Of course, there’s Nathaniel Kahn’s great film that was nominated for an Oscar. It’s a big controversial film because Louis Kahn is a big, big, big name in architecture and the narrative is fascinating. It’s mostly a son’s journey to find out who this guy was who’s supposed to be famous. In many ways, my writing is done in the same way. It’s a journey of discovery and finding things out about my father that I not only didn’t know about but never really apprehended.

I have been in correspondence with many people who have similarly well-known architect fathers. From David Stein whose father was Joseph Allen Stein, Richard Neutra’s son, Raymond, Shudra Raje, and others. This whole business of having well-known architect fathers is a problem for all of us. What to do with the question of inheritance is a daily problem and I’m just talking about mid-century modernist architects who mostly are South Asian.. I’m very interested in the idea of fathers and sons and fathers and daughters and mothers and daughters and sons and what families do with inherited passions/professions. I think it’s a big, but precise, question, in particular, today because our father’s generation-particularly in the Indian context- has passed, so now their work is under threat. Internationally mid-century modernism or brutalism, 50’s and 60’s architecture is being replaced and destroyed all over the world. So it feels like a moment of questioning an inheritance that is also under threat. How do we engage that question without it becoming about preservation purely because a person is famous or because they are our parents? I’m my own person and I’m doing other things. I teach fashion, I do interdisciplinary work, I’m Associate Dean. I keep insisting I have my own life. But, this business of inheriting modernism doesn’t leave its hold on my life.

Was there anything that was a surprise to you?

The defining narrative of my father’s career story, traditionally, was that he went to the UK, studied to be an architect, came back to India and worked with the big, famous people like Pierre Jeanneret and Le Corbusier, and then developed his urban plans in contestation with ideas of these big people. That’s the narrative he told about his own life and the one that I heard.

But, as I was looking through his papers I found that he started to write quite a lot about his early years — before he became an architect — growing up in colonial India before independence. He was writing in part a kind of a memoir, but also short notes here and there. He would refer a lot to that early life, which included growing up in a small farming town, his extended family, and growing up with a lot of animals in and around the house. He also wrote about growing up with life events like his mother and brothers dying young — their deaths connected with early industrialization as a lot of them died from tuberculosis from working in British factories and cloth Mills, which were not properly ventilated. Later on in his work when he was making his utopian urban plans, there’s a huge valorization of animals and their value to society and how they should be central to cities and the importance of that.

I tried to write this book also as a sort of a life of the person, rather than just his professional projects.

I discovered, and in the book I tried to narrate, that in many ways his life story is also about trying to come to terms with the facts of his childhood. What is a way in which one can have progress without the environmental loss and loss of health and life? How can a family unit be organized that isn’t just nuclear but, extended and provides freedom to individuals? The extended family question was a complicated one for him because he was grateful he had an extended family as otherwise, he had no mother. On the other hand, he felt like he was always the stepchild in the equation. His father was the big patriarch and primary breadwinner of the grand extended family and had no time for anybody. All these things I learned much more deeply and was able to connect them better to his intellectual projects which otherwise are presented very scientifically and in the terms of modern architecture.

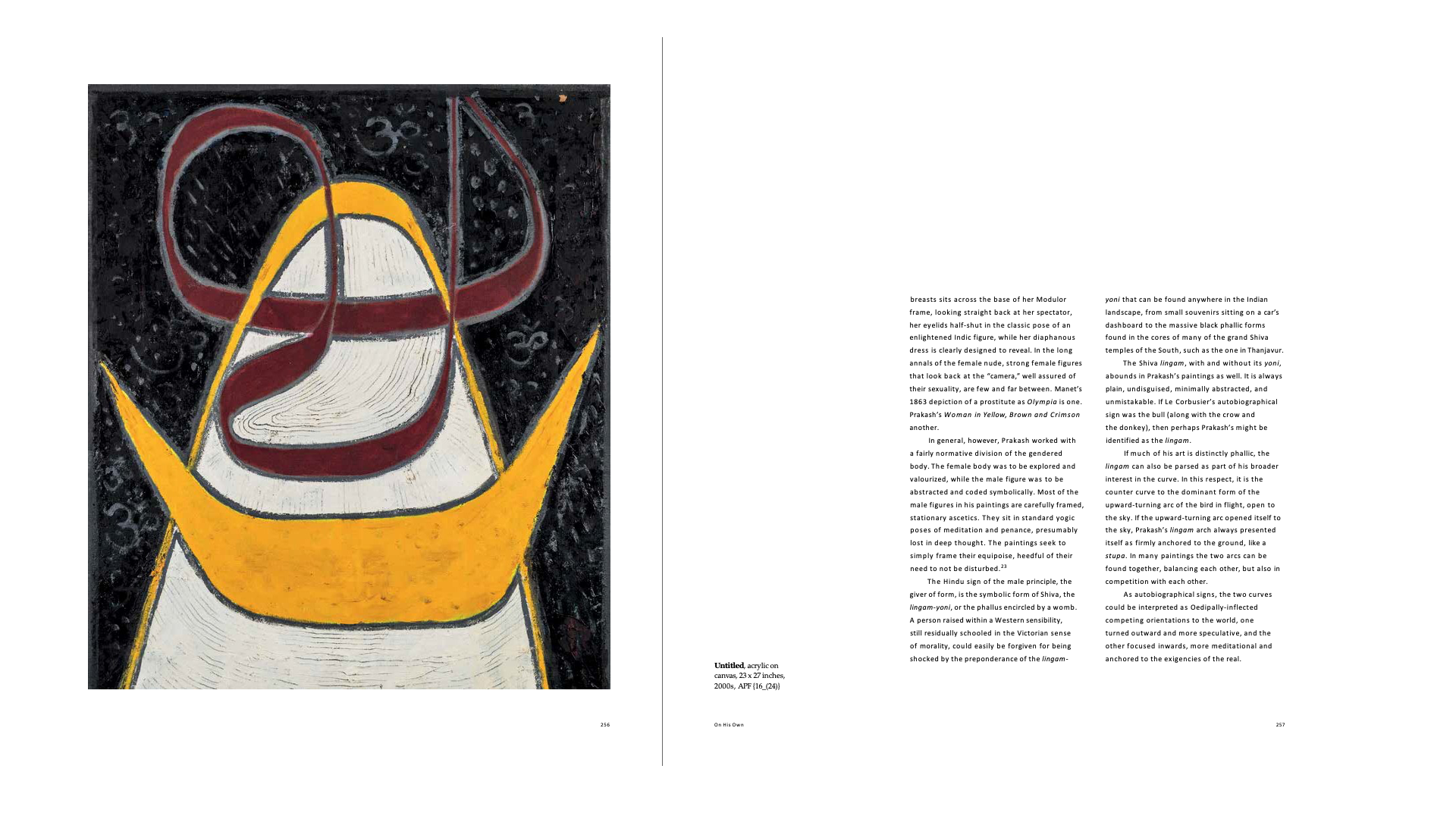

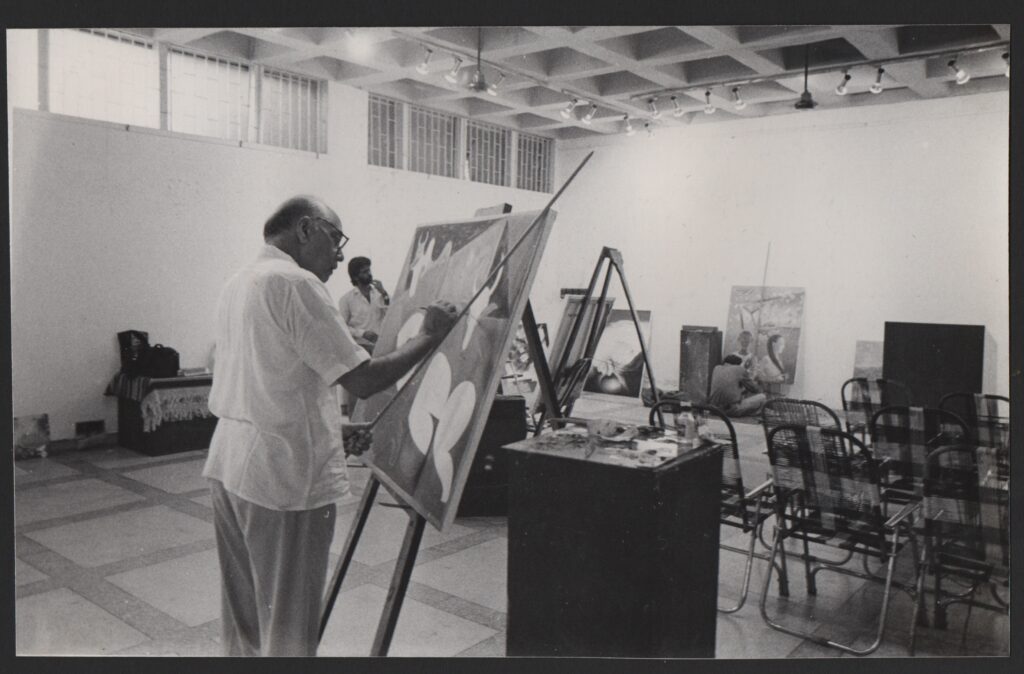

For instance, one of the things that I learned was that, really, he wanted to be a painter and an artist. But there was no real option for him as a lower-middle-class Indian male at that time. It was like ‘no way man, you gotta get a real job’. So he went on to become an architect because it was similar to drawing. In the end, he was a good architect and he worked hard at it. He made around 50 to 60 buildings, but throughout he was secretly painting or painting at night or joining art school in the evening. Then once he felt a little confidence when he was in his late 30s and well established in his profession, he started to paint formally. He painted every morning and whenever he had time. He also made sculptures and did photography and theater, and all these other things.

Once he retired from public life, which is mandatory in India, at age 58, he became an artist painter. Just before he died, he told me that the best years of his life had been when he wasn’t working formally and had just been painting.

I learned a lot about him, you know, he left me all his journals. He wrote journals from the early 1940s, particularly into the 50s, when he was a single man in the UK.

Did the fact that your father was an architect influence your decision to become one?

So this story that I narrated about how he wanted to be an artist…it’s a bit of self-projection, because in many ways I feel I wanted to be a writer and novelist and also sort of had to become an architect. Growing up with him and with big architectural names in Chandigarh and being in a city designed by Le Corbusier, there was just architecture all around. My father was also the Dean of the School of Architecture so architecture was all around me. My sister did architecture, she’s older than me, so the one kid had already done it so there was enough of that already. My father never directly expected me to do architecture, but I remember as a kid growing up since he was the Dean, people would show up — to this world-famous architectural city — from around the world in our living room. Architects from all over the world, well-known architects. I remember growing up with them sitting around in the living room arguing about architecture in big voices with the smell of scotch and cigarettes flowing in the air.

I just wanted to be part of that conversation and that sort of milieu and I pretty soon realized that that milieu is only in academics, it’s not there so much in the actual profession.

That’s how I became an architect and ultimately an academic. By the way, my father was never very happy with me becoming an academic!

He never thought of academics as ‘the real thing’.

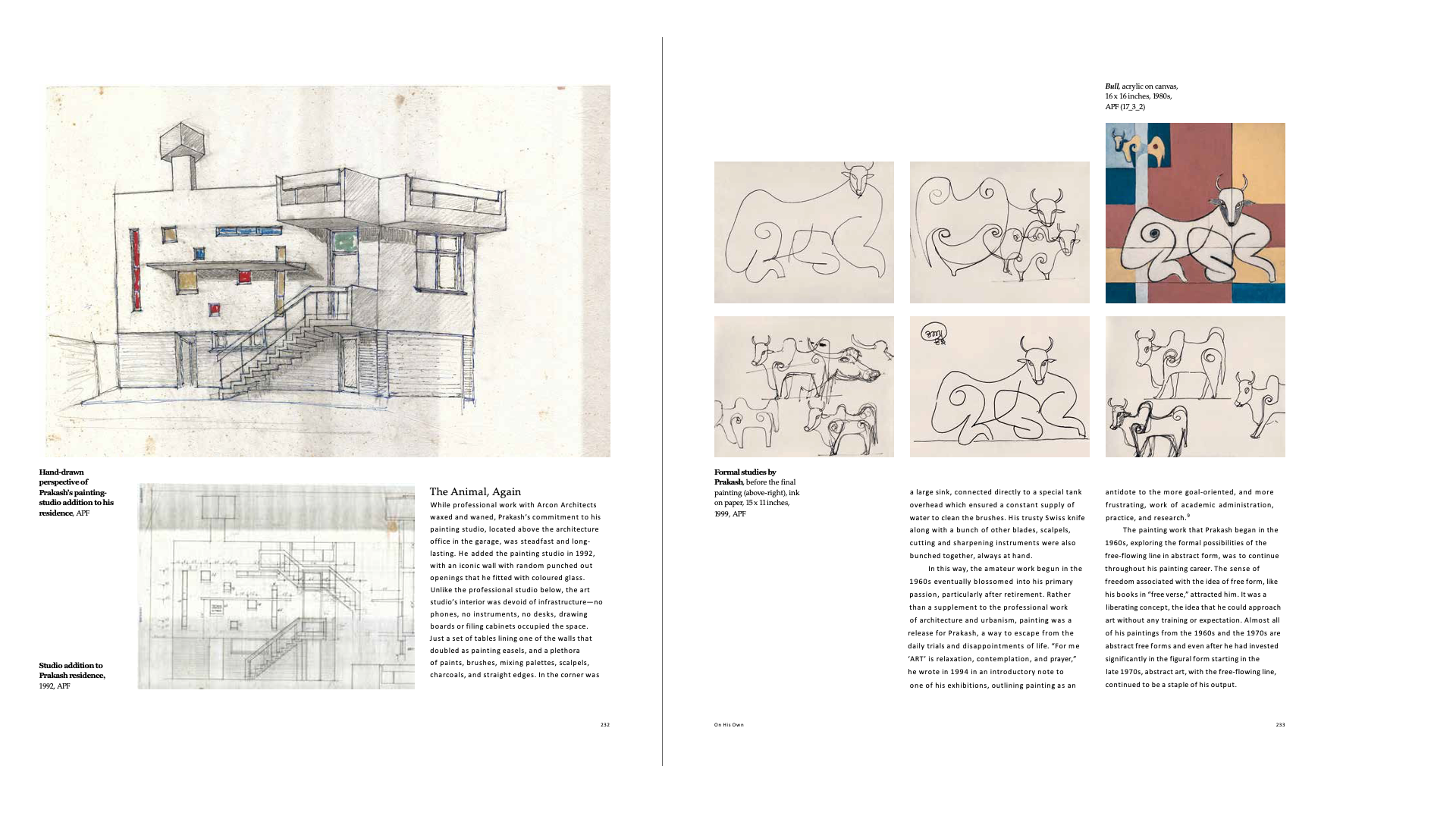

Hand-drawn perspective of Prakash’s painting studio addition to his residence, Studio additionto Prakash residence, Formal studies by Prakash before the final painting

Do all of your father’s archives and journals make you want to do the same thing and leave something behind?

Not really, no. It’s a good question though. It certainly raises the question of if somebody was going to write a similar book about me what they would say. My instinct is to say, it’s not worth writing that book. But it certainly provokes some thinking in my head around that question. I start with a kind of evaluation of his work in the last chapter and luckily, I found an essay by him evaluating his own life so I was able to critique that. So the question would be how would I do the same thing?

I was talking to a friend of mine about this and his opinion was that you think you’ve got to do a lot in your life still and that simply is a feeling that is never going to go away because you can’t see all the things you already are. A good question. I don’t have an answer.

What’s next?

I hope to organize an exhibition and maybe some lectures around the book. Beyond that, I’m hoping this just goes into the public realm. It’s for other people now who have more distance and can look at his work more objectively and critically.